- Home

- Sophie B. Watson

Cadillac Couches Page 2

Cadillac Couches Read online

Page 2

There were families who had been coming for twenty-five years, since the very first festival. Singing “Four Strong Winds” on closing night at the top of your lungs was practically a universal Edmonton experience. Once you got past the mosquitoes, toxic porta-potties, mud, and patchouli miasma, the Edmonton Folk Fest was the best of its kind Canada-wide. Admittedly Vancouver had the ocean, and the North Country Fair in northern Alberta had the homegrown, middle-of-nowhere bonus, but E-town really had the perfect combination of river valley, prairie sky, and grassy hills.

The beer garden, a central feature, was a cordoned-off section of the park with picnic benches and canopies, for shelter from sun or rain, where you plowed through beer and scoped cuties. The danger was going in for one and then staying there all weekend and never seeing any music. Two beers into our first beer garden shift we perfected our plan. Finn was the chief of operations. An unassuming CEO, he was endearing in his standard gear: a New York Rangers baseball cap, vintage Hawaiian shirt, ginger stubble, and freckles. His plan was two-pronged: 1) impromptu all the way 2) imagine we are Hunter S., Annie Leibovitz, and Tallulah Bankhead (H.A.T.). Isobel’s role was clearly the best: she just exuded her natural air of importance and decadence.

9:35 AM: We reported to the sterile, khaki, safari-looking media tent. In my pre-interview day scenario-izing I had envisioned a gigantic tent full of press people milling about, where nobody would notice me and my straw hat. But this tent was the kind you go camping in with your boyfriend (maybe) and dog (possibly), if it was a small dog, or small boyfriend, for that matter. The tent was full of hardcore types, looking like foreign war correspondents in their khaki multi-pocket pants and utility vests carrying tripods, bipods, pods, and fifteen hundred lenses. They were screamingly legitimate-looking. It must have been the khaki. Us though—the Bern Baby Bern Operation, with my orange overall shorts, blue bandana around my neck, and general ironic cowgirl chic and Isobel’s high-heel disaster—looked at worst like hacks from a small-town weekly or at best university journalists (neither would garner a lot of respect from the Khakis). We hadn’t scripted anything beforehand, having agreed we would leave it all to our natural wit and alcohol.

The only reason I was pretending to be the photographer and Finn got to be the writer was because I might suffer from stress muteness during the interview. Finn, after all, had actually worked for a real magazine, and Isobel didn’t have a nerve problem. To calm down and stop myself from flailing my arms in anticipation, I strolled around the tent while Finn lined up to talk to the coordinator girl with the hippie skirt. Isobel got busy looking bored and sexy. Unfortunately a lap took almost no time in this pup tent—if I circled more than three times, they were going to think I had a disorder of some kind—so I concentrated on looking serious, ready to speak journo at any point. As I stared at a map of the river valley, Finn stepped up to bat.

“Finn Hingley, PLEASED TO MEET YOU. JOHN, from Tilt in Torono, got in touch with CINDY last week and told her he’d be sending myself, my colleague, and my photographer to do a think-piece on DAN BERN.”

Coordinator Girl: “Hi, I’m Ursula . . . Ya, I think I saw you on the list . . . so, you guys from TO?” I could recognize a bit of that small-town defensiveness that all we E-towners have.

“YUP, JUST FLEW IN.”

“Great, well, just pick a time on the board where that girl with the huge hat is and sign up. I think he still has a slot open.”

When I looked under Dan Bern’s name, every slot was checked off; he was full for the day. I felt winded by the blow. Finn came up beside me and smiled like I was a stranger. He saw the look of despair on my face, looked at the board, and lightning fast he grabbed the Jiffy marker and made a whole new row. He wrote Tilt Magazine, Toronto and put two serious-looking asterisks beside it. We now had the new last opening of the day.

He walked back over to the girl and reached out his hand to shake hers. “Hey, thanks a lot, we really appreciate the last-minute thing—YOU’RE DOING A GREAT JOB HERE. Are you going to be able to catch Bern’s set? You really should, ya know.”

“No, I doubt it, I’m committed to Stage 5. Ron Sexsmith. Same timeslot, you know how it is. But, uh, listen, do you have a card or a copy of the mag?”

“OH SHIT . . .” He slapped himself on the forehead. “No . . . sorry, they screwed up with our luggage at the airport. But we’ll send the Folk Fest office a copy of the issue when it comes out. Should I forward it to your attention?”

It was a good recovery, but Finn was right, we should’ve picked up a copy at 7-Eleven. Was that skepticism in her eyes? Did she know? Would she tell?

We exited the tent one at a time, so as to not look too eager. As soon as we were out of her sight line we high-fived it one more time. The gesture was starting to become a compulsive thing, our collective nervous tic.

10:00 AM–2:00 PM-ish: The three of us spent the sunny hours roaming the grounds, checking out workshops. Each of us wore unusually large black sunglasses just in case we’d bump into people who might blow our cover by accident. Between Isobel and me, we probably knew half of Edmonton, so we had no alternative but to snub people. We had to focus on our mission. I was convinced the coordinator girl was going to get on her walkie-talkie and then some Security Guy with cartoon Popeye muscles and a fog horn was gonna start yelling in front of all of Edmonton: “STOP THOSE FAKES, THEY’RE NOT FROM TORONTO; THEY’RE NOT REAL JOURNALISTS; TWO OF THEM WORK AT RIGOLETTO’S DOWNTOWN AND THE OTHER ONE IS UNEMPLOYED!” We’d be hopelessly exposed. The trauma, the trauma . . .

Dan’s afternoon show on Stage 4 was a raging success. Mid-way through his concert, he had the whole crowded hill giving him a standing ovation. His song “True Revolutionaries” was the big hit.

And in Berkeley

And in Greenwich Village

And in Paris

And in Scottsbluff, Nebraska

No one sits around funky little coffee shops

anymore

Talking revolution

They get a Starbucks to go

They go back to their basketball games

Where they see who can jump higher

Who can jam

Who can take it to the rack

And they all wear baseball caps

’Cept they don’t say Yankees or Dodgers or

Cardinals anymore

They say Nike; Reebok; Adidas

Because the pro players don’t play for teams

anymore

They play for shoe companies

I was so happy to see him play again. It rebustled my spirit. The man could give you shivers one note in. He was a new kind of protest singer, not corny, not overly earnest, but wry and swaggering. He juggled songs about baseball with ones about Henry Miller and Van Gogh. He navigated a fusion between literary and macho sports stuff. He wasn’t just a set of gorgeous biceps; the man could think and had obviously read some books. But it was his next song, “Jerusalem” that sent me off the deep end and straight to the ground, unconscious.

2:30 PM: Back on my feet, I was revived, the fainting episode way behind me—three Big Rocks inside me. Isobel was off buying jewellery and summer dresses she didn’t need in the big tent while I stooged out back in the beer garden and Blue Rodeo sweetly played mountain love songs on the mainstage. There were speakers in the tent, so you wouldn’t miss the music if you were stuck there. Under the feverish sun, sky-high poplar treetops gave us serene shady spots. Five flavours of beer flowed non-stop from keg spouts into pitchers and plastic glasses. Happy people puttered about, like children on the beach. You could hear a hum of “ahhhh”: the rapture of the beer garden scene. Collective contentment that was the essence of the folk festival—never-ending good times. A fuzzy, sunshine beery haze eclipsed my paranoia. I pointed my face up at the sun—to hell with the danger—my skin drank the sunbeams and I felt warm all through my chest and heart, legs and toes. I looked at the inside skin of my eyelids and dwelled in the orange until I felt like I was inside a ta

ngerine. I forgot about my towering student loans, my nerve problem, my fainting issue, my lack of direction, Sullivan. Gorging on music and sunshine, what could be better?! Plus, I was going to interview Dan Bern later.

3:50 PM: Fearless Finn was off getting Dan Bern, and I was sitting alone at a picnic bench, as far away as possible from other beer garden dwellers. I was scared back into sobriety and felt a little dizzy from all the sun. Plus I had tumultuous guts—intestines gurgling in waves of fraudulence all the while writhing with small bubbles of righteousness—I was a freelance writer—I wrote (in my journal) and I was free. Ya! Granted I wasn’t a photographer and Tilt didn’t specifically commission Finn to cover this piece. But, I mean, c’mon: “the survival of folk music in an increasingly electronic/ironic age,” it was a totally plausible hook, even if a little pretentious.

3:51 PM: I was starting to doubt that we were actually doing this. My body couldn’t help but to express my disbelief; my fidgeting was getting out of hand. I wrestled with my postures. I couldn’t decide if I should put my bag on the table, take out the camera, hold a pen, have a smoke, scratch my head, look in a mirror to make sure I didn’t have any green onion cake stuck in my teeth. I fixated on my hair, making sure my badly positioned cowlick right at the top of my skull wasn’t doing its standing ovation. Before I could censor myself, I dipped my finger in my beer and tried to flatten the rogue strands. I wondered if the Princess Leia hairdo was a good choice for today.

I objected to that groupie word. Guys didn’t get called groupies, fan was a much better tag. I think the first big crazy fans were those bobby-soxers who went goofy over Frank Sinatra. I guess I must be a descendant of that tribe. But at least I wasn’t like those nutbars on Bern’s website; those people were rabid. It’s just like he explained in his “Abduction” song. After he returns home from the alien spaceship where he’d been abducted, he sang:

Well, my life’s back to normal now

I do the things I always do

’Cept once a week I meet with 12

Other folks who’ve been abducted too

I tell my story

They tell theirs

I don’t believe them, though

3:53 PM: What if someone came to sit down? This was exhausting. I needed to prepare, dammit. Should I take out my pens and paper? Despite the nerves, I had a feeling that I would look back on this as a great adventure as soon as it was over. I was already looking forward to being nostalgic. This was my first caper for ages as far I could remember—barring those you have on a smoked salmon pizza.

Just then I caught sight of the last person in the world I wanted to see. I squinted.

Not him . . .

Shittttt.

Better hide, I couldn’t explain that I was suddenly a photographer. Bern Baby Bern hadn’t properly accounted for civilian sightings.

Why did he always look so good?

I suppose he wasn’t everybody’s type. His tanned skin, his slender toes poking out of his ratty tennis shoes, his wild dark eyes and longish floppy black hair that usually smelled of campfire smoke. It was his eyes that got you. Sultry, come-fuck-me eyes.

I bent down to tie my shoe. I realized I had no laces, so I stroked a couple of blades of grass.

“Hey, Annie, how’s it going?”

“Fantastic.”

“You enjoying yourself? Seen any good bands?”

“Ya.”

He looked at me, weirdly, and I wondered if there was any possible way he could know what I was up to.

“That’s a pretty fancy camera you got there?”

“Uh, well . . . actually, ya . . . I’m kind of a rock journalist . . . photographer . . . for the day anyway, you know . . .”

“Really? Cool . . . How did that happen?”

“I gotta pee.”

4:00 PM: I hid by a falafel tent for a while. I just wanted to be cool. This had the makings of being pretty cool. I think Sullivan probably noticed how cool I was with all my gear. Or maybe really lame. We were behaving like total weirdoes. Everyone else was happily sitting on their ass watching music. But us, we were in the heart of the action. Maybe Dan would notice how cool I was and we could hang out and I don’t know, maybe I’d find something to do on the tour bus when he was gigging. I could be a real photographer. The technical side of cameras always buffaloed me, but I was excellent with a Polaroid. Point and shoot, baby, point and shoot!

I was sweating with the strain of trying to look casual and relaxed and natural. Should I go check my hair? There were no mirrors in the porta-potties. Where was Isobel? I lit another smoke, and put a mint in my mouth to counteract tobacco breath, then worried about the combination giving me mouth cancer. In a worried blur I watched the falafel man roll his little dumpling balls and drop them into the deep fryer one after another like a Zen master.

God, Finn was brave. Isobel was brilliant too, not being at all nervous. There must have been something wrong with me to be so nervous. It was hard to believe we were going to actually meet him. For real.

I knew I shouldn’t keep thinking I’m nervous. I’m nervous. I’m really really nervous. Nervous nervousnervousnervousnervousnerrrrrrrrrrvusususususus us nerve us. What did it mean . . . nerve us?

I was looking at myself in my pocket mirror every couple of minutes. This happens when I panic, I start to feel at odds with my body. Like my soul is floating away. Badly attached. Disembodied. However you want to call it, I stare and stare at myself trying to attach the image to my soul. It’s not an easy fit.

I changed my mantra to: I’m calm. I’m relaxed. I’m super cool and super suave and what . . . the hell is that? Bird shit on my sleeve?

That is so unattractive.

I walked back to the Bern Baby Bern headquarters picnic bench, which was miraculously free. Sullivan was nowhere in the vicinity. I pulled out the novel I was packing, Ana Karenina, my favourite love story after A Room with a View. It was a bit tragic with her pelting herself on the train tracks, but boy oh boy was it romantic.

4:00 PM-ish: “Hey,” said Isobel just as I was contemplating potential exits. I could see myself taking the fence if I took a running leap. Meeting a hero really wasn’t for the meek.

“Tell me when they’re coming, I can’t look,” I said and put on my big glasses again.

“C’est vraiment dommage they don’t serve Kir Royales here. I mean, a little bubbly would be parfait in this setting . . . Oh look, ils sont là bas. ETA: une minute. Is that bird kaka on your shirt?” Isobel asked. “Don’t worry, this is just like the time we did that stakeout when I was trying to seduce that Ukrainian guy, do you souviens? What was his code name, Ski?”

It’s true, we did have a bit of a history of stakeouts and harmless stalking. Accidentally bumping into people was my personal specialty. But I couldn’t muster any of the nonchalance I needed for this. Man, I wished I was up on the hill, stoned and happily watching Blue Rodeo. I felt nauseated.

But I couldn’t abandon Finn.

More than anything, I wanted desperately to go home to my couch and my fuzzy blanket. But I was stuck, the only thing I could do was act completely disinterested as I watched Finn walk up to the table with Dan Bern.

Mister Dan Bern.

I pretended to fiddle with a camera lens; I took another gulp of beer.

He was right in front of me.

He wasn’t your average lanky rock star, he was big and had peachy-tanned guitar-muscled arms, angel-food-cake-blond-coloured hair, stubbly face. He was gorgeous in a Californian surfer dude kind of way. I looked over at Finn; he looked unbearably nervous. You could almost see individual nerves dancing just beneath his skin. Finn sat down, and Dan headed to the porta-potties for the pre-interview pee.

“Oh man, it’s not going well, is it,” I said, noticing the hundreds of crazy sweat bubbles reproducing by the minute on Finn’s forehead.

“Shite . . . he’s not very talkative. I gave him the Tilt spiel on the way over and all I got was uh-huhs. We got really co

nfused because he thought I said Spliff instead of Tilt.”

I realized then how terrible it could be—the full scope of the horror. If Finn couldn’t charm him, we were hooped.

Not having a proper strategy was moronic. We weren’t improv veterans.

Isobel got up and dashed off. She was too fast for me, though I considered trying to lasso her with my bag strap.

Dan ambled back over to the table. He looked like he was dreading it.

“Dan Bern, this is Annie Jones, photographer for Tilt Magazine.”

“Hi. I’m a big fan,” I said, standing up and sticking out my hand, knowing it was probably clammy.

“Hey,” he said, shaking my hand.

Did I feel an antagonistic vibe?

“Let’s sit,” Finn said.

I poured us four pints of Big Rock from the pitcher and pressed play on my professional-looking little tape recorder.

“Who’s the fourth beer for? Do y’all have like, I dunno, an invisible friend or somethin?” Dan joked.

Finn and I laughed way too loudly. It was a horrible, staccato burst: HA HA HA HA.

We looked at each other and stopped laughing.

Then it was all silent except for the angry wasp circling my beer.

I couldn’t possibly start the interview, so I gave Finn what I hoped was a serious, let’s-get-to-work kind of a nod.

“Ya, our colleague just went missing. But we don’t want to waste your time, so we’ll get started. So, uh, what do you think about protest songs in this day and age, it seems like the only way they can happen is if they’re ironic, why is that? Like your song ‘True Revolutionaries,’ it’s great, but is it the audience that changes the interpretation of it or is it you? I don’t know . . . I don’t know,” said Finn, looking confused but earnest.

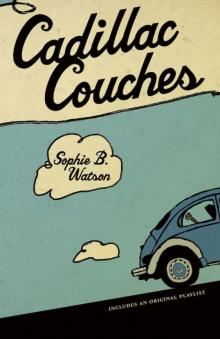

Cadillac Couches

Cadillac Couches